Politicians have been laying down the law about what clothes we can wear since the Middle Ages, and it’s only getting worse, according to a US law professor. Of all the freedoms enjoyed by Westerners, the ability to wear what we like, without government interference, is probably the one we take for granted more than any other. Most people don’t even think about it.

“We do like to feel that when we get up in the morning and get dressed we are only limited by our closet,” says Ruthann Robson, a professor at City University New York. But, argues Robson in her new book Dressing Constitutionally: Hierarchy, Sexuality, and Democracy from Our Hairstyles to Our Shoes, there are far more restrictions than we might think.

It all dates back to so-called sumptuary laws, used from the Middle Ages onwards to keep the lower orders in their place – or strengthen national identity – by dictating the style and quality of clothing citizens of every rank could wear. An Englishman caught wearing a kilt during the Scottish uprisings could find themselves arrested and thrown on to the next boat to America, explained Robson in a lecture at London’s City University.

What Not to wear

- The first written Greek legal code, in the 7th Century BC banned a woman from wearing gold jewels and embroidered robes “unless she was a professed and public prostitute”.

- Men were banned from wearing gold rings and “those effeminate robes woven in the city of Miletus”

- In Ancient Rome various laws were passed to prevent excessive expense (sumptus) in dress, such as costly Tyrian purple dye

- By the 13th Century sumptuary laws forcing people to dress according to their social status were widespread

- The 1732 Hat Act banned American colonists from wearing US made headgear

- Germany had many sumptuary laws – including a banning some citizens from wearing “very wide trousers”

- Workhouses in Victorian Britain made inmates wear drab clothing and a standard haircut to make them recognizable to the public

‘Nation’s morals’

But even here they were not safe from the English Parliament’s fashion police. The 1732 Hat Act, banning American-made headgear, rendered colonists of the New World worse off than slaves, fumed Thomas Jefferson (whose own alleged fashion crimes ranged from being too “foppish” to dressing like a Frenchman).

Things were infinitely worse for actual slaves, of course, who were banned from wearing good quality fabrics or accepting “hand-me-downs” from their masters. Such was the obsession with clothing styles that a national dress code was almost included in the US Constitution. “People thought that would be good for the morals of the nation,” says Robson.

And, with the US courts seemingly clogged up with sartorial disputes, things have not really changed, she argues. Her book and its accompanying website add up to a rogues gallery of petty local officials and judges armed with tape measures or school boards obsessing over the length of cheerleaders’ skirts.

“There are ways in which they fetishize clothes and give lots of measurements, how short can a skirt be, how low pants can be and measure them. “It really harkens back to Tudor sumptuary laws where there was a lot measurement of how big people’s ruffs could be around their neck.”

‘Thug image’

In 1463, for example, the English Parliament passed a law prohibiting men from wearing short coats and gowns that did not cover “privy members and buttocks”. In July 2013, Wildwood, a seaside resort in New Jersey, banned the wearing of trousers or swimming trunks that sink three inches below the hips, exposing bare skin or underwear.

Anyone falling foul of the “family friendly” new law, which applies to the town’s seafront boardwalk, faces a fine of up to $200 and 40 hours community service. The by-law also prohibits bare feet and going shirtless after 8pm.

Mayor Ernest Troiano told Bloomberg News the sagging style glorifies the “thug” image popular in hip-hop culture, which he claimed can intimidate visitors.

“If anybody says this is racist, that’s a load of crap. It’s about decency,” he added. Mayor Trojano is by no means the first US politician to ban sagging pants or other fashion trends, such as baseball caps worn backwards, although some previous by-laws were subsequently ruled unconstitutional.

Neither is he the first to face accusations of racism. ‘Peculiar costume’ Attempts to ban “gang colours” from schools and public events such as state fairs have led to accusations of racial profiling. Protesters in support of Trayvon Martin, the unarmed Florida teenager shot dead by a neighbourhood watch volunteer, have adopted the “hoodie” he wore as a symbol of what they see as a fight for racial justice.

In years gone by, the state used sumptuary laws to prevent ethnic groups mixing. In 16th Century Ireland, Queen Elizabeth I passed laws banning native Irish dress and requiring people to dress in “civil garments” in the English style. In 1297, Englishmen in Ireland were banned from adopting Irish hairstyles.

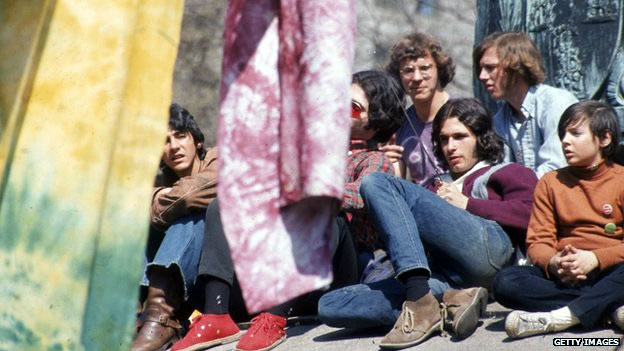

Now the state is more likely to enforce clothing regulations that encourage assimilation, as with attempts around the world to ban the Muslim full-face veil, described recently by a leading British politician as “a most peculiar costume”. Conformity was also on the minds of the US school boards who fought court battles with students in the 1960s over the length of their hair. Traditionalists appalled by the “British invasion” of long-haired rock bands, spearheaded by The Beatles, viewed this trend as unmanly, degenerate and, above all, un-American.

But with so much emphasis on expressing yourself through the clothes you wear, and formal dress codes crumbling all around us, surely we are finally free, in the West at least, to wear what we like? Robson is not so sure. “Sometimes with relaxed standards, there then comes an ability for employers to have more bias and to say that someone doesn’t look professional or doesn’t look right,” she says.

Because the rules are not written or understood. There is a problem if the rules are not written or the rules are too precise.” The only answer, she suggests, is to have no rules at all.

source: bbc